News

News

News

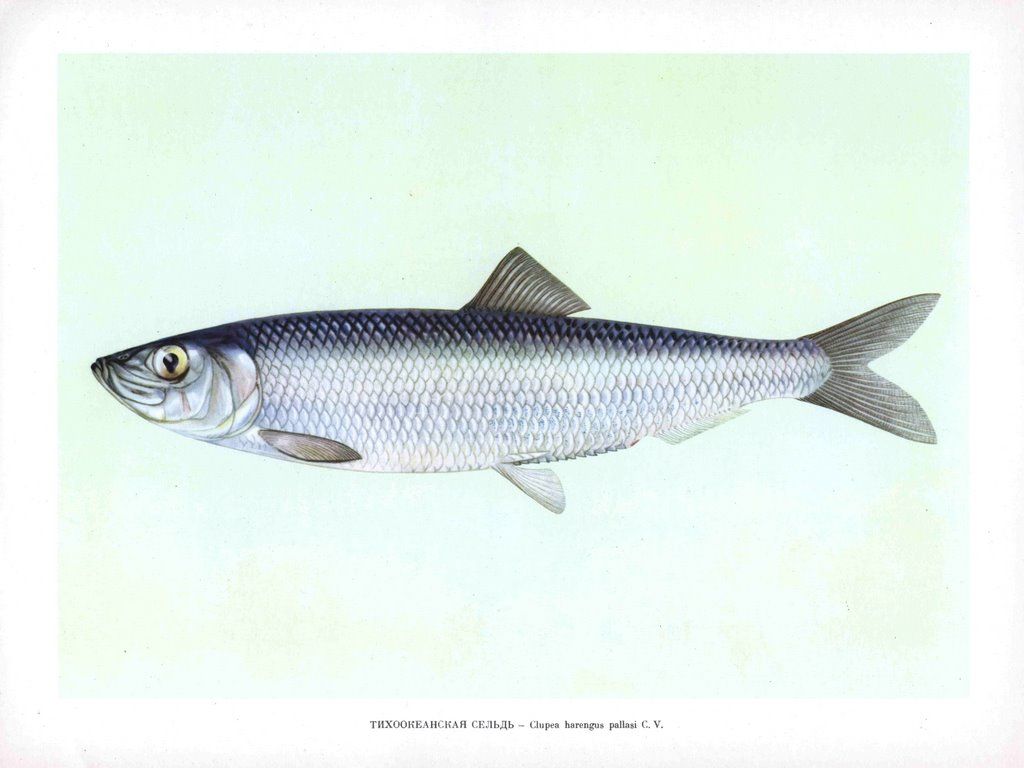

Herring in the hot seat

Herring roe are in the hot (and acidic) seat. Local researchers are studying how Herring eggs might fare with the changes we expect to see, at sea. This new research found that warmer water caused eggs to hatch faster and breathe harder. And more acidic waters increased the length of fish. Looks can be deceiving though. Researchers find that the story gets more complicated when eggs are exposed to both stressors at the same time.

Branches heavy with briny Herring eggs, Haaw da.aa in Tlingit, mark spring in Sitka Sound. Herring (and their roe) have and continue to nourish people in Southeast. Many people worry about the future of Herring and how they might persist in warmer and more acidic oceans. Lauren Bell, a PhD student with the University of California Santa Cruz, and Angela Bowers, an assistant professor at the University of Alaska Southeast, want to understand how the development of Pacific Herring roe are affected by ocean acidification and warming.

Herring spawn during a narrow window of time during the spring, when there is a lot of food available to eat. This time also corresponds with a relatively consistent range of water temperatures and pH. But what happens when the water temperature and pH change? To answer this question, researchers spawned Herring on fake and real kelp blades. Then placed the fertilized eggs into a custom-built system. This system allowed researchers to manipulate the temperature and pH of each tank. That way they could compare egg development in current and future ocean conditions.

Warmer water alone caused eggs to breath harder and hatch faster. But the number of eggs that hatched in warmer water compared to current water temperatures was about the same. Size was also impacted by warmer water. Larvae that hatched in warmer water were smaller than larvae that hatched in current temperatures. Ph seemed to have the opposite effect; larvae reared in more acidic water tended to be longer in length.

When the two stressors were put together, however, they cancelled each other out. Eggs hatched in warmer and more acidic water were the same length as fish hatched in current conditions, even though they were breathing harder and hatching quicker. Researchers have a few guesses why this might be. The added stress from both factors might cause fish to use their energy reserves quicker than normal. This might explain why we see fish in future and current conditions looking the same, despite all that stress. For future work, researchers hope to track fish into adulthood to understand if (and how) these stressors impact fish later in life.

This is important because we don’t want to assume Herring are in great condition later in life. Size might be one indicator of stress but looks can be deceptive. As we know from our own lives, unseen stress doesn’t mean unfelt stress. Vulnerability to predators and disease, caused by climate related stressors, could be as detrimental and possibly go unchecked.

By peering just below the surface, we can begin to understand how our neighbors will fare in a changing climate. A step towards increasing our own resiliency. More work is needed to understand how different stages of growth are affected by ocean acidification and warming and how habitat plays a role. For now, tiny Herring eggs provide some big insight into the future.